Summary of Comments of the Alliance of Nonprofit Mailers, MPA—The Association of Magazine Media, and Postcom—The Association for Postal Commerce

(Comments were filed at the Postal Regulatory Commission on March 20, 2017)

The Postal Service is a regulated monopoly. For this reason, the law requires the Commission to regulate the prices charged by the Postal Service for its “market dominant” mail products (products that lack effective competition). The rates set by the Commission must balance the financial needs of the Postal Service with the need to protect users of market dominant mail products from abuse of the Postal Service’s monopoly power. Since 2007, this balance has been reflected in the objectives and factors of the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act of 2006, and a statutory price cap that limits the average price increase on each class of market-dominant mail to the rate of inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index.

In this proceeding, the Postal Service asks the Commission to shatter the CPI cap, and upend the statutory balance between Postal Service and mailer interests, by allowing the Postal Service to impose above-inflation price increases on captive mailers. Without this, the Postal Service asserts, it faces financial ruin. This assertion, although unfounded, has been repeated often enough that many have come to accept it, and the possibility of a panicky and destructive “solution” to a nonexistent crisis has become an increasing threat.

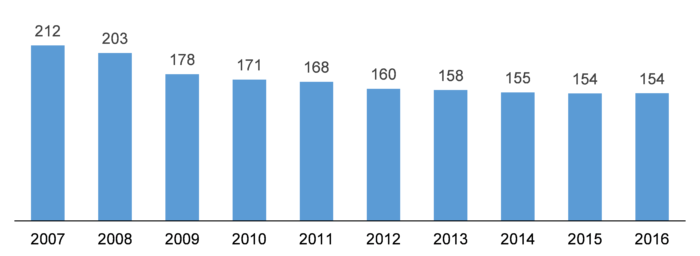

In fact, reports of the Postal Service’s impending demise are greatly exaggerated. The revenue and earnings of the Postal Service are improving, not declining. Mail volume has stabilized:

FY 2007 – FY 2016 Total Mail Volume

(Billions)

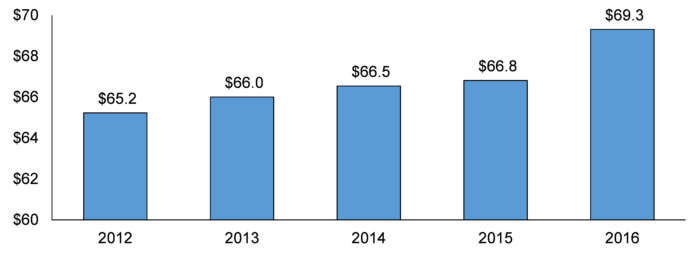

Revenue is up:

FY 2012 – FY 2016 Total Revenue

(Excluding Exigent Revenue & One-Time Revenue Adjustments)

(Billions of Dollars)

The contribution from competitive products (especially e-commerce package delivery service) has been growing rapidly:

Growth in Competitive Product Contribution

(Billions)

Operating income (i.e., income before expenditures for retiree health prefunding, amortization payments, and non-cash workers’ compensation adjustments) has been positive for the past several years. The Postal Service projects that it will earn a small profit in Fiscal Year 2017 despite the rollback of the exigent rate surcharges during Fiscal Year 2016, and, driven by continuing growth in e-commerce package delivery, revenue and earnings should be increasing over the next few years even without major productivity initiatives.

These facts refute the Postal Service’s claim that continuing growth in the number of delivery points makes a CPI cap unworkable.

The Postal Service also has healthy liquidity. It has about $8 billion of cash, and it generated approximately $3 billion of cash from operations each year from Fiscal Years 2014 to 2016 to fund investments. This cash reserve is several times the average cash reserve held by the Postal Service since 1995.

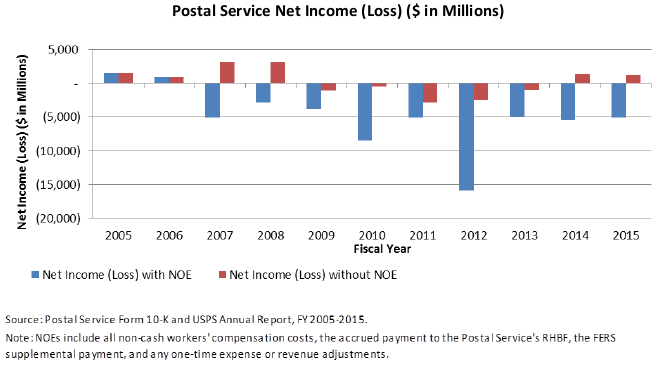

While the net earnings reported by the Postal Service are still negative, this is an artifact of the arbitrary payment schedule enacted by Congress in 2006 to prefund quickly the Postal Service’s future liabilities for pension and health benefits for its retirees:

The prepayment schedule—more than $5 billion a year—proved to be too rapid for the Postal Service to meet, and Congress has not enforced it. The Postal Service’s failure to meet an impossible prepayment schedule proves nothing about the Postal Service’s actual financial health. These are the facts:

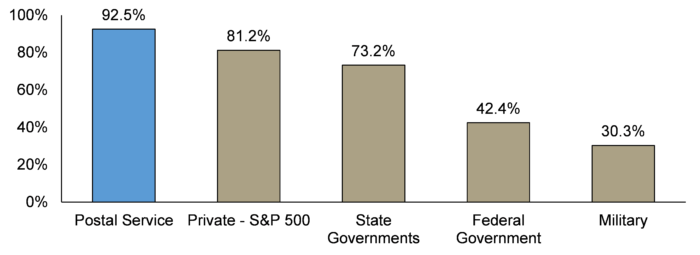

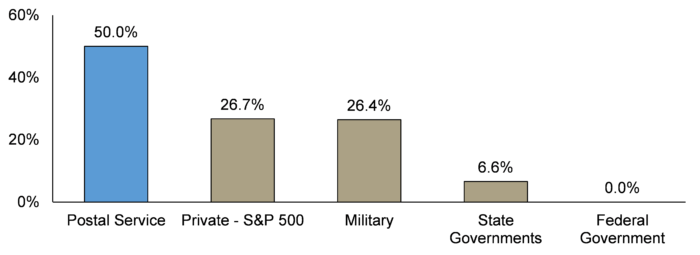

(1) Meeting the 2006 prepayment schedule was unnecessary. The Postal Service’s pension and retiree health benefit funds now have $340 billion in assets. Even according to the conservative assumptions of the Office of Personnel Management (“OPM”), this is enough money to cover 92.5 percent of the projected liabilities of the Postal Service’s pension funds, plus about 50 percent of the projected liabilities of the Retiree Health Benefit Fund. The Postal Service’s pension funds are more fully funded than the corresponding retiree benefit plans offered by the vast majority of government and private sector employers in the United States.

The same is true of the Postal Service’s retiree health care benefit fund:

Indeed, the Postal Service’s retiree benefit accounts are well enough funded that they could pay the full amount of the pensions and retiree health benefits promised to postal retirees for decades even in in the implausible event that the Postal Service shut down tomorrow and made no further contributions to the funds.

(2) The Postal Service funding percentages noted in the previous paragraph reflect OPM’s projections of future spending on pension and retiree health care benefits. These projections, however, are highly conservative, meaning that the Postal Service’s pension and retiree health benefit plans are even more richly funded than the OPM-derived figures cited in the previous paragraph indicate.

(3) The Postal Service’s financial statements understate its true financial strength in a second respect: they value the Postal Service’s real estate at depreciated historical cost (also known as “book” cost). The Postal Service acquired most of its real estate years or decades ago. Book cost understates the current value of commercial real estate because commercial real estate prices have been rising on average for decades. Although the use of book costs is generally accepted for financial reports, it is not appropriate here. The purpose of valuing the Postal Service’s real estate in the present context is not to determine the profitability of the enterprise as a going concern, or the size of the Postal Service’s rate base for cost-of-service rate regulation, but to assess the ability of the Postal Service’s assets to serve as a backstop source of funds to pay the Postal Service’s debts to its employees, retirees and other creditors in the hypothetical (and unlikely) event that the Postal Service failed and was liquidated. For that purpose, the current market value of the Postal Service’s real estate and other assets provides a more realistic measure than book costs of how much money could be raised by selling the assets.

Determining the precise difference between the book and current market value of the Postal Service’s real estate would require a valuation study. In 2012, however, the Postal Service’s Office of Inspector General estimated that the difference was about $70 billion. The disparity may be higher today; commercial real estate prices have risen on average about 40 percent since 2012.

(4) If the Postal Service genuinely believes that its finances need improvement, there are ample ways to achieve this under current law. Here are a few major options:

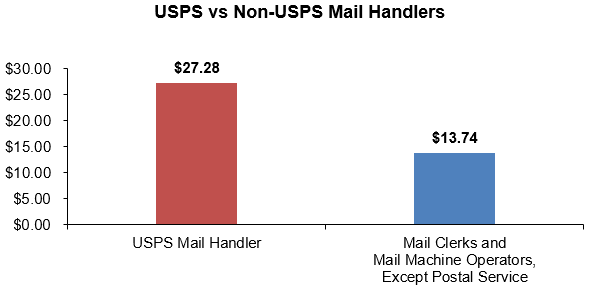

Narrow the employee compensation premium. Although the law establishes a policy that postal workers should receive compensation that is comparable to the compensation and benefits paid for “comparable levels of work in the private sector,” postal employees continue to enjoy a massive compensation premium over the private sector. By some estimates, postal workers receive nearly twice the compensation per hour that private firms offer for comparable work:

Unsurprisingly, the career postal work force has extraordinarily low quit rates—a fraction of one percent per year. These quit rates—a tiny fraction of the quit rates for private sector jobs and other government jobs—underscore the richness of the compensation that the Postal Service offers. Even a small annual narrowing of the compensation premium in future years would dramatically improve the Postal Service’s finances.

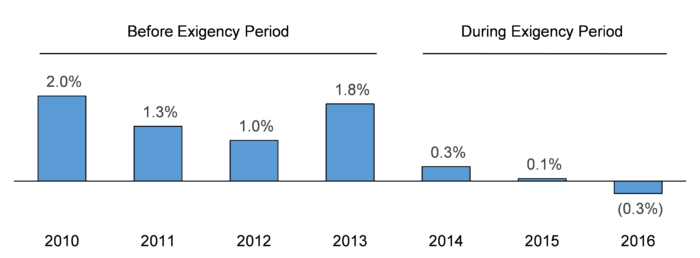

Improve operating efficiency. The Postal Service’s productivity has been stagnant for the last three years and, in fact, declined last year:

USPS Total Factor Productivity (TFP) Growth Rates

(FY 2010 – FY 2016)

Yet, as the Government Accountability Office has noted, the Postal Service has no new major cost saving initiatives planned. Before demanding the right to squeeze more money from captive mailers, the Postal Service needs to revive its cost saving efforts and make serious progress in rationalizing its mail sorting network and converting addresses to lower cost delivery modes.

Make better management and pricing decisions. The Postal Service needs to stop needlessly driving up its costs through bad management and pricing decisions such as those involving the Flat Sequencing System (“FSS”). When the FSS was still in the planning stage, experts both inside and outside the Postal Service warned that the FSS was unlikely to achieve its goals and was likely to increase, not decrease, the costs of processing and delivering flat-shaped mail. The Postal Service nonetheless chose to go forward with the FSS. Its performance has been even worse than the skeptics warned. The Postal Service should face reality, mothball the FSS, and promote efficiency by increasing the rate discounts offered for carrier route presorting from under 60 percent to 100 percent of the cost savings from this preparation. Doing this would stimulate a massive surge in co-mailing, enabling Periodicals Mail and Marketing Mail Flats to cover most if not all of their reported costs.

Show more creativity and resourcefulness in attracting new revenue. Instead of demanding the right to squeeze more revenue from captive mailers through above-CPI rate increases, the Postal Service needs to develop voluntary sources of additional revenue. In setting prices and identifying new sources of revenue, the Postal Service has operated under the 2006 legislation much like under prior law. This stasis is not what Congress intended. The Postal Service should be taking advantage of the tools created by the 2006 law (such as a streamlined Negotiated Service Agreement process) and evaluating fundamentally new sources of revenue, such as displaying advertising on mail trucks and buildings.

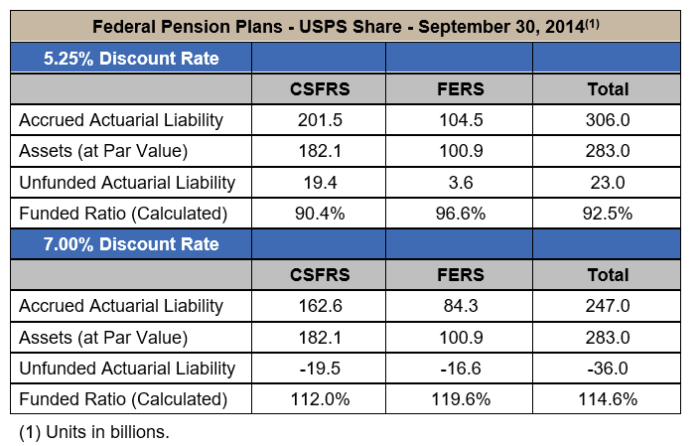

(5) Congress also has several ways to improve the Postal Service’s finances through legislation. For instance, there is no rational justification for requiring the Postal Service to invest its massive cash reserves in low-yielding Treasury bonds. Most state and municipal government employers and most private employers are allowed to invest the cash in their retiree benefit funds in a diversified mix of stocks, bonds and other assets that generate higher returns. Allowing the Postal Service to do the same would improve its balance sheet by more than $100 billion. Among other things, the Postal Service’s pension plans would become more than fully funded:

(With a 7% discount rate assumption, the USPS plans would be 114.6% funded.)

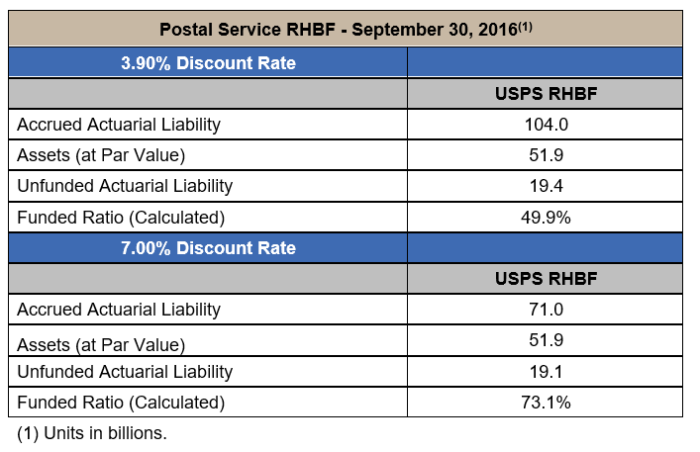

Likewise, the funding level of the Postal Service’s retiree health benefit fund would rise from about 50% to about 73%:

Additionally, Congress could integrate the Postal Service’s retiree health programs with Medicare. Although the Postal Service contributes to Medicare for its employees, about a quarter of postal retirees and their dependents do not enroll in it, forcing the Postal Service to pay extra to provide duplicate insurance coverage to these individuals. The Postal Service has estimated that this would essentially eliminate the Postal Service’s unfunded retiree health benefit liability and reduce expenses by $16.8 billion over the next five years.

* * *

By contrast, precipitously “solving” the Postal Service’s finances by allowing it to impose above-CPI rate increases on mail products would be a devastating mistake. The CPI cap is the only effective protection offered to mailers and consumers by the current system of market dominant price regulation against abuse of the Postal Service’s market power. The massive rate increases imposed by Royal Mail on its captive customers when price cap regulation was weakened confirms this.

Allowing above-CPI rate increases would also undermine both the will and the ability of Postal Service management to bargain effectively with postal labor and other interest groups that want to raise the Postal Service’s costs. Experience teaches that the Postal Service avoids spending the management resources and political capital needed to cut costs unless forced to do so. The loss of momentum in the Postal Service’s cost cutting efforts (in both collective bargaining and productivity initiatives) as the 2007-2009 recession has receded into the past illustrates this. So does the experience of light-handed rate regulation of foreign postal operators. Allowing the Postal Service to extract more money from captive mailers would not improve the Postal Service’s financial stability: the past performance of the Postal Service and its foreign counterparts shows that the extra funds would be squandered through laxer control of costs.

These outcomes would violate multiple factors and objectives of the 2006 law. As noted above, the law did not elevate revenue adequacy to an absolute good superior to all other objectives of the law. The law balances the interests of the regulated monopoly against the interests of its ratepayers and the public. Shattering the CPI cap—the only significant protection offered to market-dominant mailers against abuse of the Postal Service’s market power—to solve a nonexistent financial crisis would abdicate the Commission’s obligation to balance the interests of the Postal Service with the interests of its captive customers and ultimate consumers.

The Commission should take the following steps. First, it should find that the current system of regulation properly balances the objectives and factors of the 2006 law, issue a report to that effect, and close this docket. Second, the Commission should begin an investigation of the current market value of the Postal Service’s real estate. Third, the Commission should direct the Postal Service to prepare plans for dealing with the labor compensation premium and initiating other major cost reduction initiatives. Fourth, the Commission should recommend to Congress that it (a) relax the current restrictions on assets in which the Postal Service may invest its cash, and (b) integrate the Postal Service’s retiree health benefit systems with Medicare. The Commission is always free to revisit its findings about the performance of the regulatory system in the future if Postal Service’s circumstances change. But now is not the time for the Commission to go wobbly.

Leave a Reply