April 24, 2019

Recently, the Postal Regulatory Commission released its “Financial Analysis” report on the U.S. Postal Service’s results for fiscal year 2018. The press release is here, and the full report here.

Inappropriate Reporting

The PRC report is based on USPS financial results and 10-K reports. The Postal Service is required to report its finances using Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). The law also requires USPS to issue standard reports, such as the 10-K, that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) mandates for all publicly-traded companies operating in the U.S.

GAAP and SEC reporting are two linchpins of our capitalist system, especially when it comes to publicly-traded securities issued by companies. Requiring them, and enforcing accurate compliance, are the main ways our system ensures transparency, consistency, and accuracy, so that investors in public companies can make informed decisions.

We have been thinking for some time that, although well-intentioned, requiring GAAP/SEC reporting by USPS, and making evaluations and policy based on them, is not really a good fit. The PRC Financial Analysis report only brought this thought to the fore.

What we have is one government agency evaluating another government agency using reporting and analysis designed for very different kinds of organizations with very different purposes. And the main reason to have GAAP/SEC reporting is to enable investments in the companies, not policy for a large, public service agency.

Private Sector Use of GAAP/SEC is Different

It is also very important to understand that in striving for consistency, GAAP/SEC reports do not always tell the full story about an organization’s finances. Just because a report follows consistent rules does not mean it gives a fair and complete picture of reality. And when you apply them to a very different and unique organization like USPS, the possibility for misleading or incomplete reports only increases.

In the private-sector, publicly-traded world, there exists a massive, thriving industry of financial analysts, economists, and securities analysts whose job is to make sense out of all the GAAP/SEC reporting that comes out. These analysts issue their own reports and opinions that are based on deep dives into the data, and adjustments made to reflect what their expertise says is closest to the reality that investors should base decisions on.

In turn, the SEC keeps a close eye on the analysts to make sure they are not purposely or inadvertently misleading investors. And independent nonprofit associations like the CFA Institute issue hard-earned charters and enforce ethics standards for the professionals who evaluate the GAAP/SEC reports.

So, not only does the postal world use reporting that is designed for completely different organizations and purposes; it also lacks the independent analytical industry that augments the reports in the private sector. Readers of USPS GAAP/SEC reports are correct to feel cognitive dissonance. They just don’t make sense, or provide a way forward.

PRC Financial Analysis

The PRC Financial Analysis report is a valiant effort to try to fill the gap. But as much as we support the PRC in its mission, and admire all the strides is continues to make, it really cannot fit a square peg in a round hole. As a regulator and a government agency, we believe the PRC feels that it should not do the type of deep dive and re-thinking that the private sector analytical industry does for public companies.

Most of the PRC FA report is a very comprehensive and accurate retelling of the USPS financial reports of FY 2018. Lacking is a critical eye toward ferreting out what important facts that GAAP/SEC consistency leaves out. When big negative trends or events appear, the PRC notes them, but does not analyze why they happened, whether they should have happened, and whether they are likely to continue.

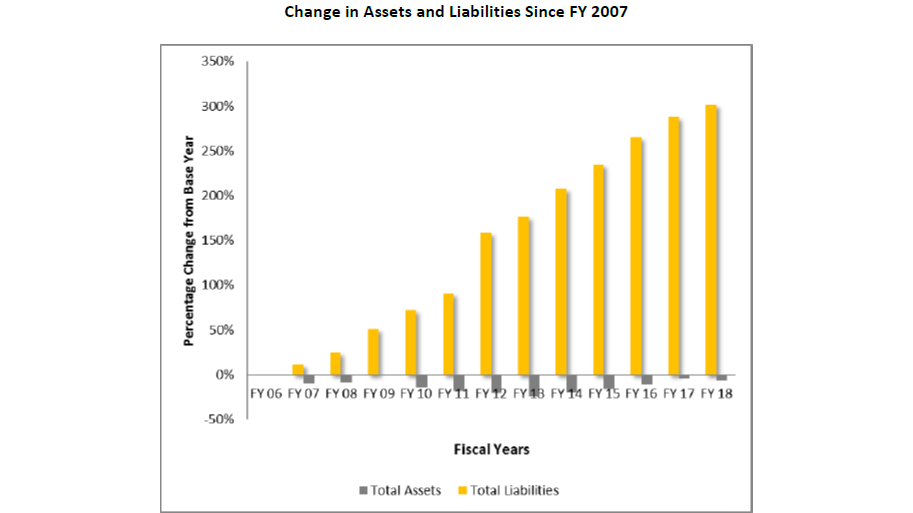

A major example of the need to dig deeper is the balance sheet. If you just look at the reported numbers, and assume it’s a private sector company, you panic. But if you look below the surface a bit, you realize why the reported numbers look so bad and are not really an accurate picture of the financial strength of the USPS.

In short, the reported assets are artificially low, and the reported liabilities are artificially high. The fact that they are in compliance with GAAP/SEC is nice to know but not really relevant to the reality of USPS. And there is something very wrong with refusal to look beyond the GAAP/SEC numbers, if, in fact, anyone insists on that.

The assets are artificially low mainly because the largest USPS asset is real estate. It must be one of the largest real estate owners in the U.S. And it has owned the real estate for a long time. Sure, GAAP requires that financial statements report real estate at cost less depreciation. But if you are trying your best to estimate the true value of USPS, you should know the current market value of its real estate. Much of the value can be tapped even in an ongoing operation, through closures, consolidations, and sale/leasebacks.

Reported liabilities are less than accurate for several reasons. They are mostly rough estimates of potential future costs for postal retirees’ pensions and health care insurance. The estimates depend on many assumptions, including future health care costs, future numbers of employees and retirees, future inflation, future investment returns, life expectancies, and future collective bargaining agreements. (It is sadly ironic that most of USPS liabilities are based on estimates, while no one estimates the value of its largest asset.)

The largest estimated unfunded liability, retiree health benefits, could be brought into positive territory with two standard industry practices. First, require all postal employees to use Medicare as their primary health insurance. And second, invest the postal retiree funds at normal market returns rather than artificially low non-marketable Treasury securities. (It also is sadly ironic that some insist on standard practice using only GAAP/SEC reporting, but ignore the nonstandard practice in actually managing the liabilities.)

Bottom line: Trying to fix the Postal Service by fixing its unadjusted GAAP balance sheet would be trying to solve the wrong problem.

Examples

One of many examples of the potential pitfalls of using inaccurate balance sheet data is in the PRC focus on liquidity ratios. On pages 69-72, the regulator displays all of the usual liquidity ratios, all of which look terrible. They describe a risk as: “An increasing current liability ratio value is generally a sign of financial pressure because it indicates growth in the proportion of liabilities that must be paid within 1 year.”

The Postal Service and the PRC include as bills due within a year the previously unpaid $33 billion in pre-funding of retiree health benefits. And these unpaid RHB bills represent half of all USPS “current liabilities.” Congress unfortunately included in the 2006 PAEA law a ten-year prefunding schedule that USPS had no capability of fulfilling. And they haven’t been paying them. And no one is asking or demanding that they pay them in the next year.

The widely-agreed upon needed action is to reschedule the pre-funding to a reasonable 40 years, not to base policy on inaccurate “liquidity ratios.” Indeed, publishing inaccurate liquidity ratios misrepresents the true condition of USPS and could lead to the wrong “solutions.”

Private sector analysts would want to dig deeper into why certain USPS operating results are going in the wrong direction, rather than simply accepting the operator’s story.

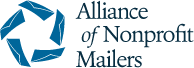

Example: Why has USPS productivity gone south in the past five years. The PRC Financial Analysis reports the drop in productivity, but does not question it or seek answers. Negative productivity would be a major red flag for any private sector analyst. They would want to know whether it is a trend that will continue or a short-term blip.

Rather than delving into root causes, the PRC elsewhere in the report states: “Consumer price index (CPI)-based price increases were not enough to offset revenue lost from declining volumes.” The CPI price cap has been a known parameter for 12 years. Why not ask what is preventing productivity improvements from offsetting volume declines?

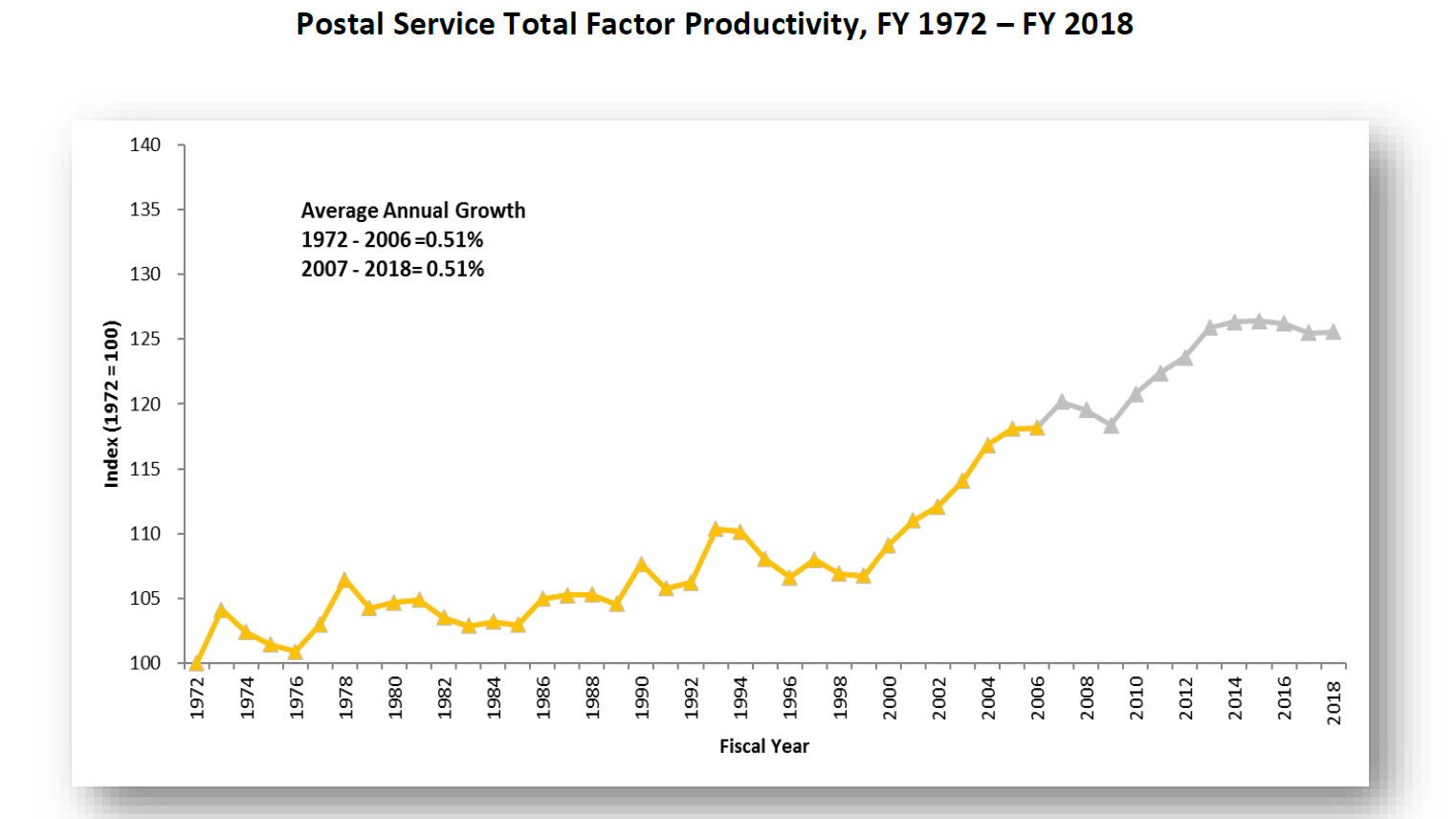

Example: Analysts would want to know why, with declining volume, a reduction of 10,000 employees, personnel making up 74 percent of total costs, USPS has increased its use of work hours over the last four years. The only explanation given by USPS in the PRC report is that delivery points and packages have increased.

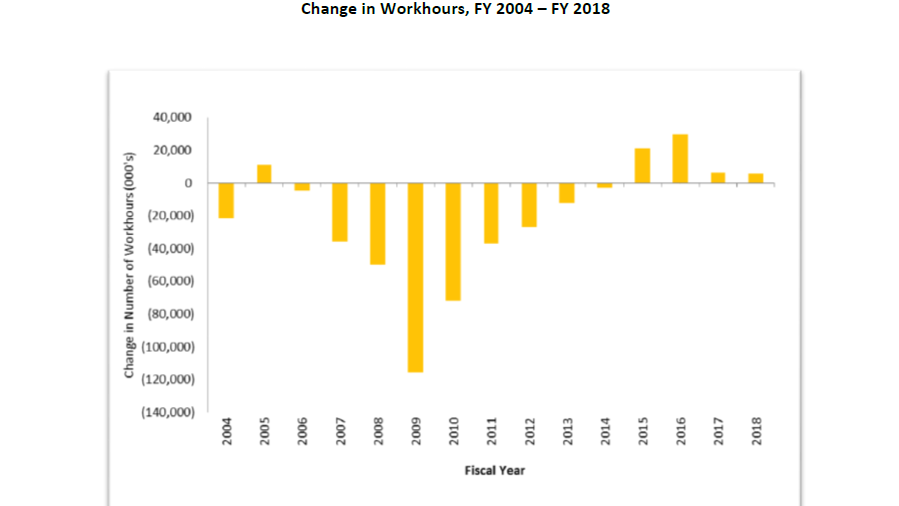

Example: Why did air transportation cost go up 16.6 percent last year? The explanation is limited to higher fuel costs and more packages. Will this continue or is it an anomaly?

The point

The real point is not to criticize the USPS or PRC, but to use financial analysis to reach accurate, actionable conclusions. Publishing rote GAAP/SEC reports and ratios without adjusting or explaining them for the unique situation of the Postal Service can cause more harm than good. Someone, please explain the usefulness of the following PRC graph.

Leave a Reply