May 3, 2018

The April 26 report issued by the PRC on FY 2017 performance said the USPS underperformed its goals in all four areas:

- High-Quality Service

- Excellent Customer Experiences

- Safe Workplace and Engaged Workforce

- Financial Health

Because the PRC is currently proposing very large rate increases for customers adding up to as much as 40 percent over five years, and basing them on financial health, we will focus on that area.

Financial Health

For financial health, USPS had two goals: one is a productivity goal for the Deliveries per Total Workhours (DPTWH) percentage change, and the other is simply controllable net income.

The USPS missed its productivity goal by a lot in FY 2017. “The FY 2017 target for the DPTWH % Change was an increase of 0.6 percent over the FY 2016 result…The FY 2017 result was a decrease of 0.5 percent and, therefore, was 1.1 percentage points lower than the FY 2017 target.”

Missing your main productivity goal, in an environment where labor costs are 80 percent and are steadily marching upward, is a big miss. For the huge drop in productivity, USPS management blamed unexpected volume declines combined with their inability to adjust their operations:

The Postal Service explains that a “rapid decrease in volume during the year contributed to [the Postal Service] missing the DPTWH target” and that the Postal Service’s large network makes it difficult to adjust workhours when faced with sudden, unexpected changes in volume. Id. The Postal Service explains that its large network of interdependent offices are (sic) governed by national collective bargaining agreements and many local agreements. Responses to CHIR No. 19, question 4.a. The Postal Service states these agreements make it “challenging for the organization to implement quick fixes to sudden and unexpected volume changes, such as those experienced in FY 2017.” Id.

Almost as surprising as the miss, is the huge turnaround USPS management is predicting for 2018:

The FY 2018 target for the DPTWH % Change represents a 2.1 percent increase over the FY 2017 result. FY 2017 Annual Report at 25. The Postal Service states it will meet the FY 2018 target by capturing workhour reductions from declining mail volume, and from operational initiatives to improve efficiency. Id.

The two most puzzling things about the big drop in postal productivity are:

- Why, after almost a decade of intense focus on declining mail volume did the USPS seem so surprised with the drop in 2017, and why, after all this time, is it unable to adjust its labor resources quickly and efficiently?

- And why does the regulator think the solution to inefficiency and lower productivity is the evisceration of the main incentive for efficiency, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) cap?

Paper Tiger

The Postal Regulatory Commission says in this report it doesn’t believe the USPS can achieve its FY 2018 productivity goal. But it also demonstrates the degree to which the Commission is a “paper tiger” when it comes to regulating Postal Service performance. The only consequence for underperformance seems to be: if USPS doesn’t make its unrealistic, unsubstantiated goal for 2018, we’ll make it explain how it plans to make its productivity goal for 2019:

The Commission appreciates that the Postal Service’s vast network presents challenges in matching workhours to workload, particularly when faced with sudden or unexpected volume changes. The planned improvement efforts articulated by the Postal Service are encouraging, and it appears likely that these efforts will improve workhour efficiency generally. However, the plans for improving performance raise a legal compliance issue. If the Postal Service does not meet a performance goal, annual performance reports must both explain why the goal was not met and describe plans and schedules for meeting the goal. 39 U.S.C. § 2804(d)(3). Because the Postal Service missed the DPTWH % Change target in FY 2017, the FY 2017 Report was required to describe plans and timelines for meeting the FY 2018 DPTWH % Change target. The Postal Service acknowledges that its plans for reducing workhours are not targeted specifically toward meeting the FY 2018 DPTWH % Change target. Thus, it is unclear how the Postal Service plans to meet the DPTWH % Change target (and, by extension, the Financial Health performance goal) in FY 2018. The Postal Service also does not identify timelines for meeting the FY 2018 DPTWH % Change target.

The Commission finds that the FY 2017 Report does not comply with 39 U.S.C. § 2804(d)(3) for the Financial Health performance goal. To comply with 39 U.S.C. § 2804(d)(3) next year, if the Postal Service does not meet the FY 2018 DPTWH % Change target, the FY 2018 Report must describe specific plans designed to meet the FY 2019 DPTWH % Change target. The FY 2019 Plan must also include timelines for implementing programs that will help meet this target.

Why is productivity so important? It makes all the difference between USPS succeeding and failing. And it requires no legislation and no PRC rules changes.

The Postal Service also uses a more comprehensive measure of productivity called Total Factor Productivity (TFP). We showed in our comments filed with the PRC that TFP has been declining in the most recent four fiscal years, after rising about one percent a year in the previous seven.

No Accident

We believe it is no accident that the drop in productivity occurred just when USPS enjoyed the exigent surcharge of $4.6 billion paid by its customers from January 2014 through April 2016.

The following table shows annual growth in TFP during the pre-exigent surcharge period, when mail volume was falling 4.2 percent a year, and annual declines in TFP in the most recent four fiscal years when the mail volume decline slowed to 1.4 percent annually.

Annual Volume Decline Annual TFP Growth

FY 2007 – FY 2013 -4.2% 0.91%

FY 2014 – FY 2017 -1.4% -0.08%

Contrary to its rationale given to the PRC in the FY 2017 Annual Performance Report, that declining volume makes it hard to be productive, USPS did much better with TFP during the seven years when mail volume was declining three times faster than the most recent four years.

The main reason productivity went into the tank is that the incentives of the CPI cap came off during 2014 through 2016. And the PRC is now proposing much bigger pricing surcharges for the next five years: CPI + 5% in many cases.

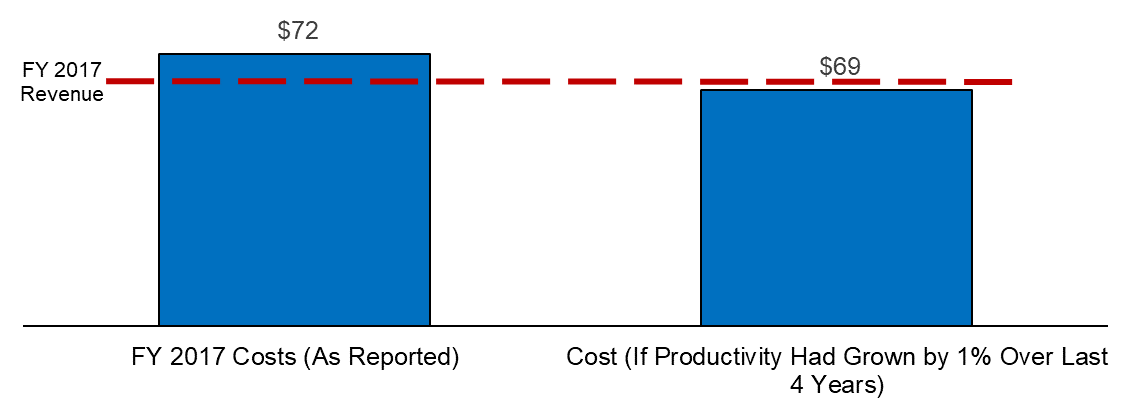

We also showed in our comments that if TFP had continued to rise at 1 percent a year during FY 2014 – FY 2017, the loss of $2.7 billion reported by the Postal Service in 2017 would have been a profit. The following chart shows that with minimal productivity growth, postal costs would not have exceeded revenue last year.

Recent history has shown that price cap regulation of a monopoly does work in providing incentives to be efficient. Without it, the regulator is left with ineffective jawboning.

Leave a Reply